The Quiet Contract

I don’t think we learned about this in Teacher Preparation. Or maybe my senses were too overwhelmed by the surfeit of stimuli from my student teaching practicum in inner city New Haven – my chainsmoking mentor teacher haranguing me in her windowless office, the beepers going off and sending students out into the halls for drug deals, my complete lack of sleep that Fall term juggling six courses of which the practicum counted as only one – to notice it at work in my borrowed classroom. When I took my first full-time teaching job in China, at Yali Middle School in Changsha, Hunan province, the exotic surprise of having 50 students leap to their feet to chant, “Good morning, Teacher Wendy!” in perfect unison when I entered the classroom each day left me little room to wonder if anything subtle were at work. But it did strike me sharply in my early days as a college teacher in Quebec.

One of the first classes I was hired to teach was at Dawson College, downtown, at night. Dawson feels like a rabbit warren inside, with weirdly low ceilings and myriad narrow passageways – in a former life, it was a convent. Among my students was a bearded white ex-marine in his 50s, and he was loudly vocal in his consternation at my choices of course texts, which included Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye – foregrounding female Black experience – and Shyam Selvadurai’s Funny Boy, a queer coming-of-age novel set during the civil war in 1980s Sri Lanka. Why, he demanded, should he care about these people’s stories? Nevertheless he dutifully read the assigned readings for each class, wrote the in-class journal reflections and essays, participated actively in group work. At the end of the course he even organized the class to take me out for drinks to thank me. Along with all the other students, when I entered the room, he was seated at his desk; when I spoke he listened; when he wanted to speak, he raised his hand and waited his turn.

On more than one occasion in more than one class I have marveled at the quiet contract at work: students dutifully play their role, even if they are silently seething inside, by coming to class and doing what I say. It is astonishing to see this in action, especially when you are a new young teacher entirely unsure of what you are doing: to recognize the respect automatically accorded the authority of the teacher. It seems to have been programmed in there, in schools all over the world.

Of course there are the odd students out who choose to test it. The boy in my English 101 who cheekily took a phone call “from the mayor” of the small Quebec town that hosts our college, and proceeded to hold a full-throated conversation while looking me straight in the eye, until I invited him to step outside. The young woman who vociferously disagreed with the mark given on a midterm assignment and attempted to rally her classmates into a kind of insurrection. The kids who quietly pass out cold on their desks, right in the front row. Normally these incidents only occur after a class has been meeting for part of the term – it’s definitely possible to breach the contract. But the break only has an impact in the context of that tacit recognition of the script that governs what all teachers and students are expected to do.

And then there is Crossroads: the program for Indigenous students in my college. It’s not like the classroom itself erupts into chaos from day one: it’s more that the quiet contract is quietly disregarded. Even on day one, there is no guarantee everyone will make it on time, or show up at all. They may or may not have books or pens or paper, and I am greeted with quizzical glances if I am foolish enough to presume that they do. I can go ahead and ask my teaching questions: there is no guarantee anyone will raise their hand to answer them. And as the term wears on, and everyone grows a little more at ease with me, the wheels may well and truly fly off the bus. Students may wander in and out of class at random moments without explanation. One student, having finally grasped that I expected some explanation when she was to be late or miss class, would eventually sustain extended messaging exchanges with me: she’d let me know she was awake on time for class, but was having a coffee; then, eating a leisurely breakfast; then, doing her makeup. On a good day, she might quietly roll in, an hour and a half into a two-hour class: always meticulously turned out, each detail of jewelry and clothing carefully chosen, long black hair beautifully groomed. Once a student arrived just in time for the last ten minutes of class, looking flustered, because she was determined to make bannock -- traditional Indigenous fried bread -- for the group, but the first batch didn’t turn out so well and so at ten, instead of coming to class, she’d had to start all over again.

The advent of cellphones and laptops has stretched this contract to the breaking point in every class, but with the Crossroads group it can border on the carnivalesque. Granted, I work with them this term in study block, which is not a regular class, although attendance is mandatory, and I am meant to create a quiet, supportive space for completing homework and in-class assignments. In a single study block period, when students were supposed to be working on an English poetry assignment, one student was using a computer to research allusions to mythological figures – fair enough. He told me, quietly, that the internet can’t really be trusted when it comes to Inuit culture and tradition. But two others were playing a gambling video game together at full volume, unabashedly, the assignment handout page wholly ignored, or left to fall to the floor. One was playing a virtual basketball game on her phone with her sister back in their home community, while simultaneously raising her hand to ask me questions about her responses on the handout. Another somewhat sheepishly showed me the results of his ChatGPT search, which was not giving him the simple answers he sought. Two others were listening to songs on headphones and singing aloud, as if blissfully unaware of their captive audience – a few of whom really were trying hard to read and write, albeit with limited success.

I work with the teachers in the program this term, attempting to guide the students to complete assignments that are, without exception, never completed during class time, no matter how carefully planned out in advance by the instructor. The English teacher reminds me of my own past struggles when he shows me a file folder full of their analytical paragraphs-in-progress: most have, at best, a few lines that simply restate the assignment topic.

“I need something I can give them a grade for,” he says. “But even though I gave them a firm deadline and told them the assignment was worth 15% of their final mark for the course, they mostly spent the class period chatting and goofing off, or looking at TikToks. Some of them aren’t even coming to class anymore.”

In all fairness, the problem is hardly the fault of the students. The quiet contract was breached back when Canada established residential schools as a means to “kill the Indian in the child.” Architects of this school system legislated that Indigenous children from the age of seven or even younger be forcibly taken from their families and sent to board in these schools, where in addition to being cut off from their families, traditions and way of life, they were systematically starved, tortured, sexually abused, and offered little by way of meaningful education. The actual mission was to gut the resolve of the Indigenous peoples -- whose lands the government wanted for its own colonial projects, like Prime Minister Sir John A. MacDonald’s vision of a railway connecting sea to sea – to fight for their rights. Back when I was a quietly seething but nevertheless obedient student in high school, we only learned about the “great unifying vision” of Sir John A. and nothing about the residential school business. I began to learn about that for myself after I had been teaching in Canada for over a decade, and had gotten to know a few of my Indigenous students, and their struggles to learn.

Arguably the mission of the Crossroads program is some kind of reconciliation through action. It’s a transitional year program, meant to welcome and support students who come from distant northern communities as well as those closer by. I have never been to the far north, but I have been learning about what life is like up there from my students. One study block, when one of them was trying to catch up on an introductory PowerPoint presentation – due over a month earlier – she showed me some slides of her home community, Puvirnituq.

“These are the trucks that bring the water” she said, showing me a huge truck beside a neat row of houses.

“You don’t have running water in your homes?” I ask.

“No—it gets too cold, so tankers come to each house. We also have trucks that come to collect –” she giggles and asks her classmate something in Inuktitut. Her friend Googles, and comes back with: “Sewage.” “Those ones are orange – see?” she asks, clicking through a series of slides.

“When I first moved to Canada from the States,” I told her, “everyone asked me if I were going to live in an igloo.”

“Oh, our community had the world record for building the biggest igloo!” She shows me pictures. “We have a big snow-sculpture competition, at the winter games, every two years. Look, that’s my uncle” she shows me a slide with a smiling man, wearing a traditional Inuit knitted hat with a tassel, next to the wall of neat snow bricks. She follows up with a series of pictures with family members, mentioning more cousins, uncles – in fact these names are applied to a much broader network than immediate blood relations. “We have the first woman mayor – Leann’s mom!” Leann has been struggling to work in the midst of the chaos and looks up, startled to hear her name. Leann has been very quiet, and expressionless, and often absent. I realize I have no idea, really, who these kids are, and the fact that they aren’t producing much in the way of written work for their English class is distinctly skewing my perceptions.

I have release from teaching a course – normally a group of over 40 students, meeting twice a week for two hours, with the attendant heaps of marking and extensive preparation – to supervise study blocks, but also to give students extra help with their English assignments and their reading and written assignments for other courses, as needed. The problem is that much of the time they pretend all is fine and they don’t need my help. It takes at least a month to build enough comfort in the room that anyone will admit to struggling. But it is now November: a few students have been sent home and many others warned that their funding will be cut off if they don’t make a point of attending every class and also maintaining a passing grade in at least some of the courses. I offer extra office hours in the Indigenous Student Resource Centre, which this term is a lovely house just off the main campus. But so far whenever I show up I wind up talking with the various support workers about student issues and needs … not meeting with the students in need themselves. We decide that I should offer office hours in the student residence, so students don’t have to leave warmth and comfort on a rainy day to seek help.

The pressure on them only continues to build: when I meet the group for study block on Friday they are checking their phones to see their grades for the midterm test they just took in a Humanities course. There are some moments of pride – one smiles broadly that he passed with a 60, another is quite pleased with his 78. But Anita, who was preparing her slide show and teaching me about Puvirnituq, is staring wanly at a desk strewn with an array of papers, books and laptop, struggling to find her way through a miscellaneous morass of overdue assignments. She knows she failed the midterm because she hadn’t done any of the assigned reading, but she glumly scrolls on her phone for confirmation of that sad fact.

Meanwhile their English teacher and I have agreed we will be strict about enforcing the no phones (or tablets, or laptops …) policy for their midterm paragraph assignment for his class, so I am actively policing the tech usage. It is like playing Whack-a-Mole. Everyone has some kind of excuse – checking for grades, changing the song they are listening to (headphones are allowed)… I remind them of my offer to give them extra supervised time for the English assignment that afternoon in residence, and it sounds like I have a few takers.

At the end of study block two of them are still actively working away at their paragraphs, but another class is coming in, so I have to hustle them out. I need a break myself, to get a coffee and go to the bathroom. When I get to residence Leann and her friend Connie are waiting for me. As it turns out, I can’t just go into the residence: a student needs to invite me as their guest. Leann lives in the residence and so is charged with “hosting” me and Connie, which means also she will have to see us out once it is time to leave.

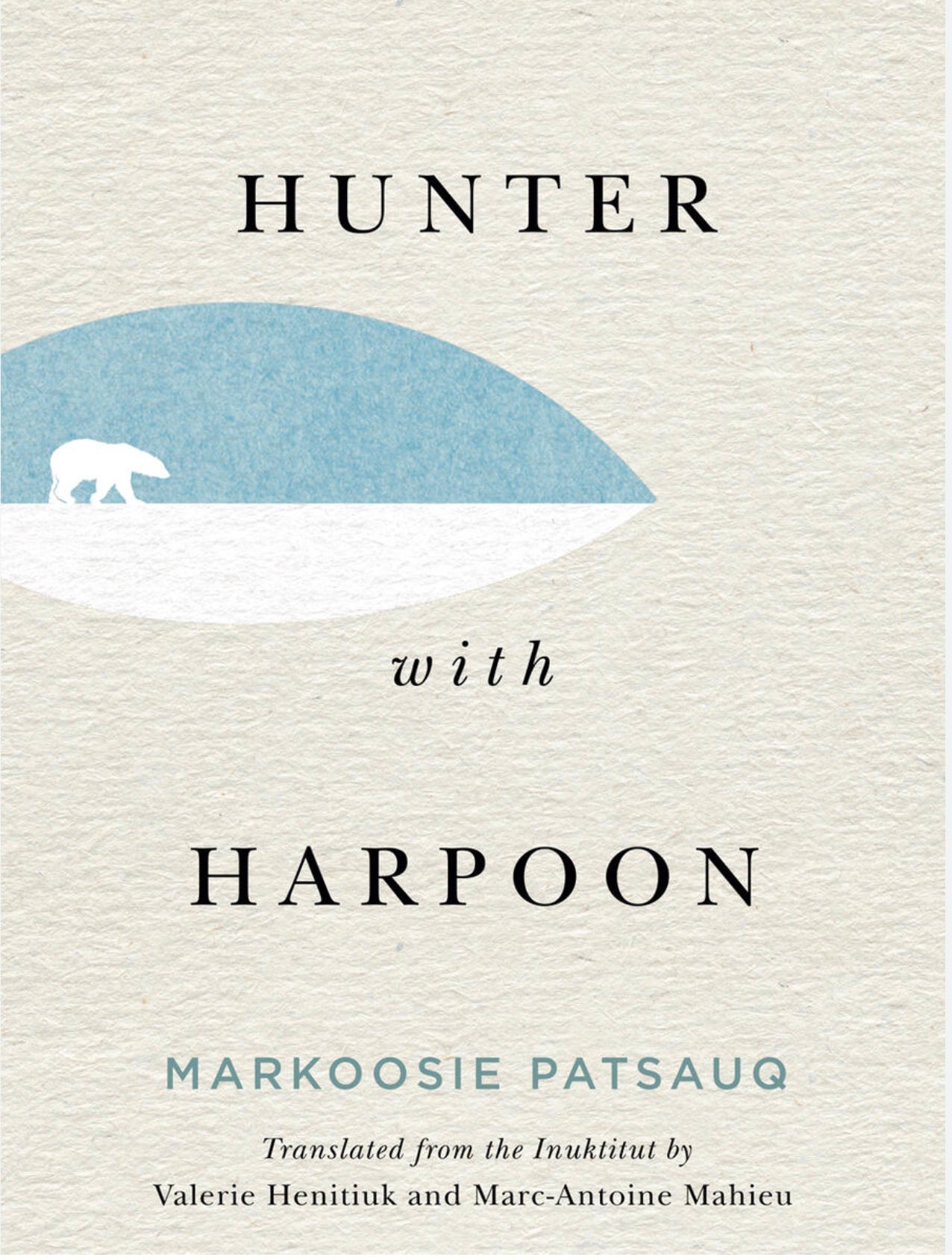

Tasked with this responsibility, Leann is suddenly more animated than I have ever seen her. She shows me what she has written so far: it is only about three sentences, although they aren’t really sentences, and I actually have a lot of trouble making sense of them. She is writing about how the main character in Hunter with Harpoon, sixteen-year-old Kamik, becomes a man through his series of encounters with polar bears in the novella. It is impossible to grasp, from her first sentence, if it is Kamik who breaks his leg in his first encounter, or the bear. When I point this out to her, she bursts out laughing. I realize I have never heard her laugh before. It is Kamik who breaks his leg, due to his inexperience, she tells me. We hammer out something that works as a clear thesis argument for her paragraph. I realize she needs a lot of help with both grammar and spelling: she is using her phone to find words, not with a dictionary app, but through an intriguing technique: she types the first part of a word into a chat window and sees what her phone suggests to complete it. It is no wonder, given the laboriousness of this process, that she has written maybe four lines of text in over an hour and a half (not counting time in English class).

“Now that you have a good thesis,” I tell her, “you just need to find three good quotations from the novel that show what you are arguing – three steps in Kamik’s progress to becoming a man through his fights with the bears.”

“OK,” she responds, with a cheerful willingness and energy I have not seen until now. She picks up her novel and starts to read – aloud. At this point it is 3:30, and I am scheduled to be available until 4. But she is focussed and committed to her work now. I check my phone to see if any other students have messaged me and sure enough, Anita has written to ask if I am at the residence yet. I message back that we are in the basement common room.

Leann has distinct trouble with pronunciation and reading fluency generally, except when it comes to words in Inuktitut, names and places I generally find almost impronounceable -- the novel was translated into English from the French translation of the original Inuktitut. Its language is fairly simple. I discover, though, when Anita arrives and starts distracting Connie and Leann with chatter, that Leann has come to English as her third language. Also, she skipped fifth grade – but not because that was what best suited her learning. “The teacher for grade five left,” Anita explained, “so they just put her whole class in with ours.” Leann, then, is a year younger than Anita – Connie, who has much stronger English writing skills and who has wrapped up the first draft of her paragraph and moved on to struggling with an online bursary application, is two years older. She, too, learned English third after Inuktitut and French.

Leann comes to a passage that clearly illustrates a next step in Kamik’s character evolution, so I shift from answering vocabulary questions and gently correcting pronunciation to discussing this with her. Strikingly, the polar bear in this next encounter takes Kamik’s father by the waist in his jaws. I was not fully aware of the size implications. Leann nods energetically. “Yes, polar bears are huge,” she says. The students seem to really enjoy this novel, which I find an incredibly bleak read, because it speaks to their lived experience, unlike pretty much everything else they are studying in college. In the battle with the bear, Kamik’s father manages to stab the bear in the haunch with his harpoon. So it was, in fact, the bear who had an injured leg – not Kamik. More laughter.

“Augh, I’m so tired!” says Anita. She has been working steadily away on her own paragraph, no phone in sight. I have never seen her get any writing done during study block. I have also never seen her put her phone away before. She reads her thesis aloud for my approval: it is simple, but clear and easy to develop, about the qualities that make a good hunter, according to the novel: he must be brave, skilled, and strong.

“Me too,” I say, in part to connect, in part because my eyelids are independently twitching with fatigue. “I’ve had a busy week. I’ve been spending a lot of time with my daughter, playing games of Sorry to distract her, when I should have been marking assignments. She just went through her first breakup – she’s about your age – and it’s been hard.”

Anita scrutinizes me. “You look tired,” she agrees. Then: “We want to know something about you.” Her attention, and that of Leann and Connie, has now been fully redirected to me. “Can you tell us, maybe, who was your first boyfriend? And do you still think about him?”

So there’s another part to the quiet contract, which I think was covered more directly in Teacher Preparation, and it has to do with boundaries – which are directly linked to maintaining classroom authority. Normally a teacher would not sit around in the basement common room of a student residence chatting about her first boyfriend with her students. Typically my romantic history is distinctly off-limits even when I am attempting to connect on a more personal, human level. However, our circumstances here are really not of the standard-issue teacher-student variety. I have a lot of terrible history to make up for to establish trust. So I go ahead and tell them about Guy, who I genuinely do still think about – and there’s quite a little soap opera there. He took me to his grade 13 formal (he was two years older than me); I ultimately distinguished myself by meeting my next boyfriend at a university party Guy had invited me to, maybe a week after our breakup, and left Guy drunk and sobbing in the kitchen when handsome Greg walked me home. Guy had gone on to marry his next girlfriend, who also went to our high school (I attended their wedding); to have a daughter (who is around their age and now at university in Montreal); and to die too young from the aftereffects of struggles with drug and alcohol addiction – struggles which are all too familiar to my students.

Weirdly, my arguable TMI seems to send them back to their tasks with renewed energy and focus. Connie comes to ask me a question about her bursary application. Leann forges on with her reading and regular consultations with me, determined to find her third quotation. Even Anita, who has completed no written work for English that I am aware of before today, is working steadily away at finding quotations and building her argument. We all have a little chat about whether “bravery” and “skill” are two distinct things, and we all agree that they definitely are, particularly in the way they are depicted in the novel: “bravery” is a state of mind, while “skill” has to do with distinct physical abilities.

I check the time, knowing I have stayed well past four: it is quarter to six. “I should really leave in about fifteen minutes,” I say. “I promised to spend this evening with my daughter. Let’s see if we can get to a good stopping place: maybe,” I turn to Leann, who has by now been working steadily for a good three hours on her paragraph, “if we can just get you set with your third quotation, then you’ll be ready to write everything up in class on Monday.”

Leann nods, smiles – I have rarely seen her smile, either: “Yes, thank you. Thank you so much for staying with us.” We arrive at the point in the text where Kamik kills his first polar bear. Leann is not that into hunting herself, she tells me, but she has hunted: beluga, caribou. It strikes me that hunting is as fundamental an aspect of Inuit culture as book-reading and essay-writing has always been to mine as the daughter of academics.

By six, Leann has carefully outlined her arguments for her paragraph and neatly put her work away. Anita packs up and heads back to her room in residence; Leann escorts Connie and myself to the exit. But Leann keeps walking with us; she and Connie discuss a plan to go get groceries for dinner. Leann continues to walk with me towards my office, through Stewart Hall, past the cafeteria and the book store, through the long corridor known as the Arctic Circle that connects the new sciences building to the old hall that houses the library and registrar. The grocery store in town had closed a year or two back; now when anyone wants to buy food they need a ride, and there is a metro and bus strike on. Leann will have to Uber to the IGA. I assume that’s why she’s continuing to walk through the college with me. But when we reach the turn off towards Penfield, which houses the English department, she and Connie turn back.

“Where do you go to get your Uber?” I ask, and she points back towards the residence. “So, wait, you were just escorting me to my office?” She nods, shyly. I am touched: it’s a little as if I were visiting her at home, and like a thoughtful hostess, she has taken the care to see me safely on my way. I want to hug her, but teacherly boundaries hold me back. So I reach out and give her arm a little squeeze – she smiles at me again, and gives me a little squeeze back.

Couldn't agree more; your nuanced observations on the quiet contracts in different educational settings really resonat, it truly makes one think.

I really like the line about hunting beluga….hunting in general…being as “native” to indigenous cultures as reading & writing is to your academic culture….it’s just something that’s done….assumed…the what one does in this world; it’s also appealing that you let your guard down with these indigenous students & that that letting down of the guard brought you closer